Originally Published Winter 2014

Reading Nikki Durkin's post "My startup failed, and this is what it feels like..." prompted me to scrape some data on the economics of incubators.

If only to expose one of the great myths surrounding this disruptive new innovation model. i.e. Once you have been invited to join an incubators like Y-Combinator or Techstars you significantly reduce your chances of failure (e.g. Why hardly any Techstars companies fail).

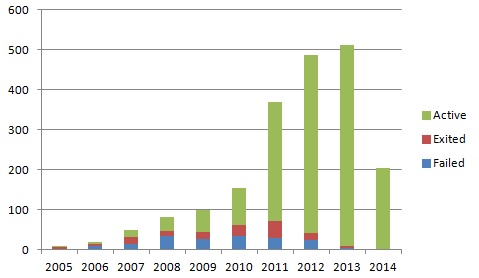

To demonstrate the how the narrative is shaped in the media I have scrapped the Seed-DB data from the top 12 start-up incubator programs.

As you can see, based on the raw number of start-ups being churned out by the incubators, the survival narrative is self evident. The failure rate pales into insignificance compared to the survivors and exits.

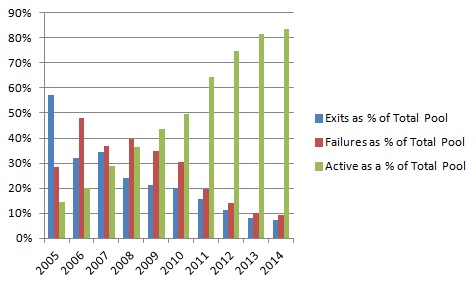

How ever things look very different once you pivot the data into a new visualisation.

As you can see the historical record suggests, even when the amount of incubator product available to the market is scarce, the failure rate dramatically increases once you factor in the time it takes to achieve an exit on the investment.

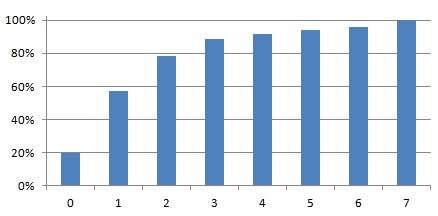

More over the probability of achieving an exit dramatically reduces after the first 2 years of operations.

The reason for the distortion is simply a function of the explosion in incubators since 2011.

Suddenly, thanks to the wave social media IPO's, everybody is investing the incubator innovation model.

Product is being released into the market faster than the historical failure rate for this type of investment.

What the historical data suggests is, rather than the incubator ecosystem being a robust, lower risk, higher margin start-up accelerator model for would be investors and entrepreneurs, the current incubator ecosystem is significantly overweight with unrealised product (i.e. start-ups) that it will struggle to exit (i.e. achieve a return on investment) over the next 3-5 years.

If, as was the case with the 2005/06 sample, a market of 26 handpicked, closely mentored and highly publicised start-ups delivered a failure rate of nearly 50% after 7 years, what are the chances of a market in excess of 500, maybe even 1000 start-ups pumped out of a global array of incubator clones, loosely modelled on the Y-Combinator model, delivering a better success rate in the next 3-5 years?

Probability suggests the failure rate should sky rocket. The 50 year average for failure across the world's technology incubators is, after all, between 97%-98%. What is there to suggest this generation of fresh young ideas will perform any better?

But that is the whole point. Incubators are not about reducing the rate of failure as a pathway to achieving success. They are about amplifying it. This is why the incubator narrative represents such a delicious paradox. 12 weeks in the casino re-imagined as an education.

For what is the incubator ecosystem if not a Monte Carlo Simulation, a dice game, played out by the placing of bets on the hopes, aspirations and talents of a generation of young entrepreneurs who struggle to comprehend the mathematics, never mind the patterns in the big data.

For the incubator and its investors is all about playing the odds. And in the Monte Carlo Simulation he, or she, who roles the dice more often than the competition, inevitably wins. For it is the sum of the roles that counts in your favour. Not the one chance you have to roll the dice.

Put simply, if you enter into this game thinking you have a winning ticket just because you have secured a spot in an incubator, you can be sure you have been well and truly played.

Copyright 2014 Digital Partners Pty Limited. All Rights Reserved.